Gunhild Borggreen

Co-Founder and Project Manager for ROCA. Associate Professor in Art History and Visual Culture, Department of Arts and Cultural Studies, University of Copenhagen.

Co-Founder and Project Manager for ROCA. Associate Professor in Art History and Visual Culture, Department of Arts and Cultural Studies, University of Copenhagen.

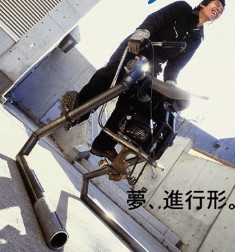

My interest in robots is closely related to my specific research on Japanese contemporary art and visual culture, and my attention to gender and national identity. During my research I have encountered the works by Japanese contemporary artists such as Yanobe Kenji, Mikami Seiko, and Hachiya Kazuhiko, who include robotic elements in their art work. I have also seen several of the Human-Robot theatre productions of Seinendan, produced as a collaboration between theatre director Hirata Oriza and robot scientist Ishiguro Hiroshi. Artworks can contribute to important discussion by posing alternative questions towards the use of technology. Some artworks may also challenge the techno-orientalist or techno-nationalist sentiment that often emerges when speaking about Japan as a social or cultural imagination.

Robots as technology

The etymological background for the word robot comes from the play R.U.R (Rossum’s Universal Robots) by Czech writer Karel Čapek in 1921 in which synthetic creations build to resemble humans take on a life of their own.

The term robot today designates a broad variety of mechanical and electronic devises, ranging from industrial robots placed at assembly lines, to zoomorphic entities seen in toys and artificial pets, anthropomorphic machines that simulate human motion, as well as androids or humanoids that resemble humans in size, surface appearance and independent agency.

Robots as technological devises occupy a special place in society and culture in regards to ethics because of robots’ close resemblance to human beings and the emphasis on autonomous agency. The quest for constructing artificial human life and intelligence is often juxtaposed by the fear of machines developing self-awareness and taking control of humans. This paradox of fascination versus fear has been the topic of a number of cultural products throughout the 20th century, such as Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein (1818) or films such as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), Ridley Scott’s science fiction film Blade Runner (1982) and Oshii Mamoru’s animation film Ghost in the Shell (1995).

Robots in Japan

Japan is considered the world’s leading robotic country, and about one third of all robots around the globe are to be found in Japan. Robot technology is associated with economic growth because of the importance of industrial robots and service robots in the Japanese society, especially in the era of economic growth in the 1970s and 1980s, as well as the ongoing research and development of various types of humanoid and virtual robots under direct government support in Japan.

Robots play a major role in popular culture, from manga characters such as Astro Boy to Paro, an interactive healing pet. The image of Japan as a robotic nation often results in claims concerning Japanese people as more positively minded toward mechanical or electronic machines in their everyday life compared to other nations. Such perceptions have given rise to the concept of Techno-Orientalism, in which Japan is constructed as the stereotype ”Other” by the West because of the alleged fear of Japan as the ”future” that transcends and displaces Western modernity.

Various robotic theories relate to vision and visuality. Japanese robotics Mori Masahiro, for example, coined the “uncanny valley” hypothesis in 1970, which many scholars link to Freud’s concept of Das Unheimliche. According to the hypothesis, humans are likely to have emphatic feelings for a robot only to a certain extend, after which repulsion take over.

Another example is the recent development of “partner robots” that rely on the robot’s visual sensing technologies in order to identify and recognize their human partner. These and similar theories point out the importance of sight and visuality to the ontology of robots – what defines a robot in terms of appearance, how and what can a robot ”see”, and how does the visual appearance influence human notions of robots?

Techno-Orientalism

Media outside Japan often report on the latest development in Japanese robot technology, and contribute to an image of Japan as a robotic nation. This may result in claims concerning Japanese people as more positively minded toward mechanical or electronic machines in their everyday life compared to other nations. Such perceptions are linked to the concept of Techno-Orientalism, in which Japan is constructed as the stereotype “Other” by the West because of the alleged fear of Japan as the “future” that transcends and displaces Western modernity.

The myth of the Japanese as “the most machine-loving people in the world” can be traced back to the 1970s at a time when Japanese industry and consumer products entered the international market and caused equal amounts of admiration and fear from the West. David Morley and Kevin Robins discuss in their book Spaces of Identity. Global Media, Electronic Landscapes and Cultural Boundaries (London: Routledge, 1995) how new technologies have become associated with the sense of Japanese identity and ethnicity. They describe the concept of “techno-orientalism” in gendered terms as they suggest that technology has been central to the “potency” of Western modernity.

The functioning and the significance of technology have been crucial for Western identity and, therefore, Japan’s advancement in the area of new technology during the 1960s became a challenge for the West. Morley and Robins argue that the West fears that “the loss of its technological hegemony may be associated with its cultural ‘emasculation’”. (Morley and Robins, Spaces of Identity, p. 167)

The critic and media activist Toshiya Ueno relates Techno-Orientalism to Orientalism as follows:

"The basis of Orientalism and xenophobia is the subordination of others in various areas of the world through a sort of 'mirror of cultural conceit'. A host of stereotypes appeared when binary oppositions -- culture and savage, modern and pre-modern , and so on -- were projected on to the geographic positions of Western and non-Western. The Orient exists in so far as the West needs it, because it brings the project of the West into focus." (Toshiya Ueno, "Japanimation and Techno-Orientalism")

My research project on the cultural dimensions of robots will include questions about whether such Techno-Orientalist notions of Japan as “robot nation” still exist today, fifteen years after Morley and Robin’s book, or if the discourse has changed due to broader perspectives of globalization.

Japanese robots in Radio 24syv

On October 7, 2015, Gunhild Borggreen talks about the Japanese artist Kimura Masa and other aspects of robots in Japan in the culture programme AK 24syv in Radio 24syv on the occasion of the Robot and Performance seminar. Listen to the interview (in Danish) here. Forward to 41:50.

Robot Bodies

New publication by Gunhild Borggreen: "Robot Bodies: Visual Transfer of the Technolgical Uncanny" in Transvisuality: The Cultural Dimension of Visuality, Vol II: Visual Organizations. Edited by Tore Kristensen, Anders Michelsen and Frauke Wiegand. From Liverpool University Press, 2015

Astro Boy in Helsingør

Saturday April 25, Gunhild Borggreen gave a talk (in Danish) with the title "Tegneserier og robotteknologi - hvorfor er japanerne så glade for robotter?" at Danmarks Tekniske Museum (Danish Museum of Science and Technology), Helsingør.

Saturday April 25, Gunhild Borggreen gave a talk (in Danish) with the title "Tegneserier og robotteknologi - hvorfor er japanerne så glade for robotter?" at Danmarks Tekniske Museum (Danish Museum of Science and Technology), Helsingør.

Asimo in the radio

The Japanese robot Asimo was shown at Experimentarium in Copenhagen April 16-19. Gunhild was interviewed in DR P1 Eftermiddag April 15.

The Japanese robot Asimo was shown at Experimentarium in Copenhagen April 16-19. Gunhild was interviewed in DR P1 Eftermiddag April 15.

Output

Listen to the DR radio program Eksistens, broadcasted in September 2012, about robots. Gunhild talks about the Uncanny valley and the cultural imagination of robots in Japan (in Danish).